By | Engku Azlan bin Engku Habib

Police in the Netherlands have an in-depth success story of bringing down a drug market from the Dark Web. This has shown the world that criminals cannot really hide in the realm of the Dark Web and get away with crime.

Efforts of combating Dark Web crime have previously involved firefighting methods. Authorities would hunt down administrators of Dark Web sites selling contraband and shut down the sites. But in a matter of days, sellers and buyers would simply migrate to the next dark-web market on the list.

This approach does not resolve the problem at all but only halts business for a few days. To put this to an end, the Dutch police made an elaborate plan to take down the popular Dark Web market Hansa in 2016. Thus Operation Bayonet was conceived.

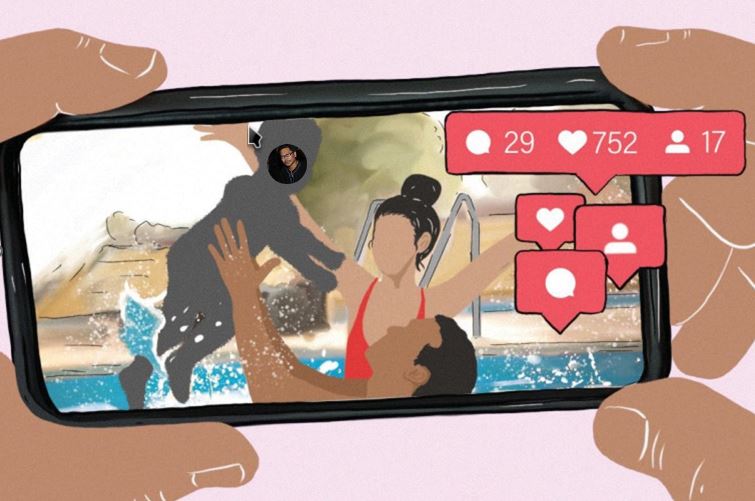

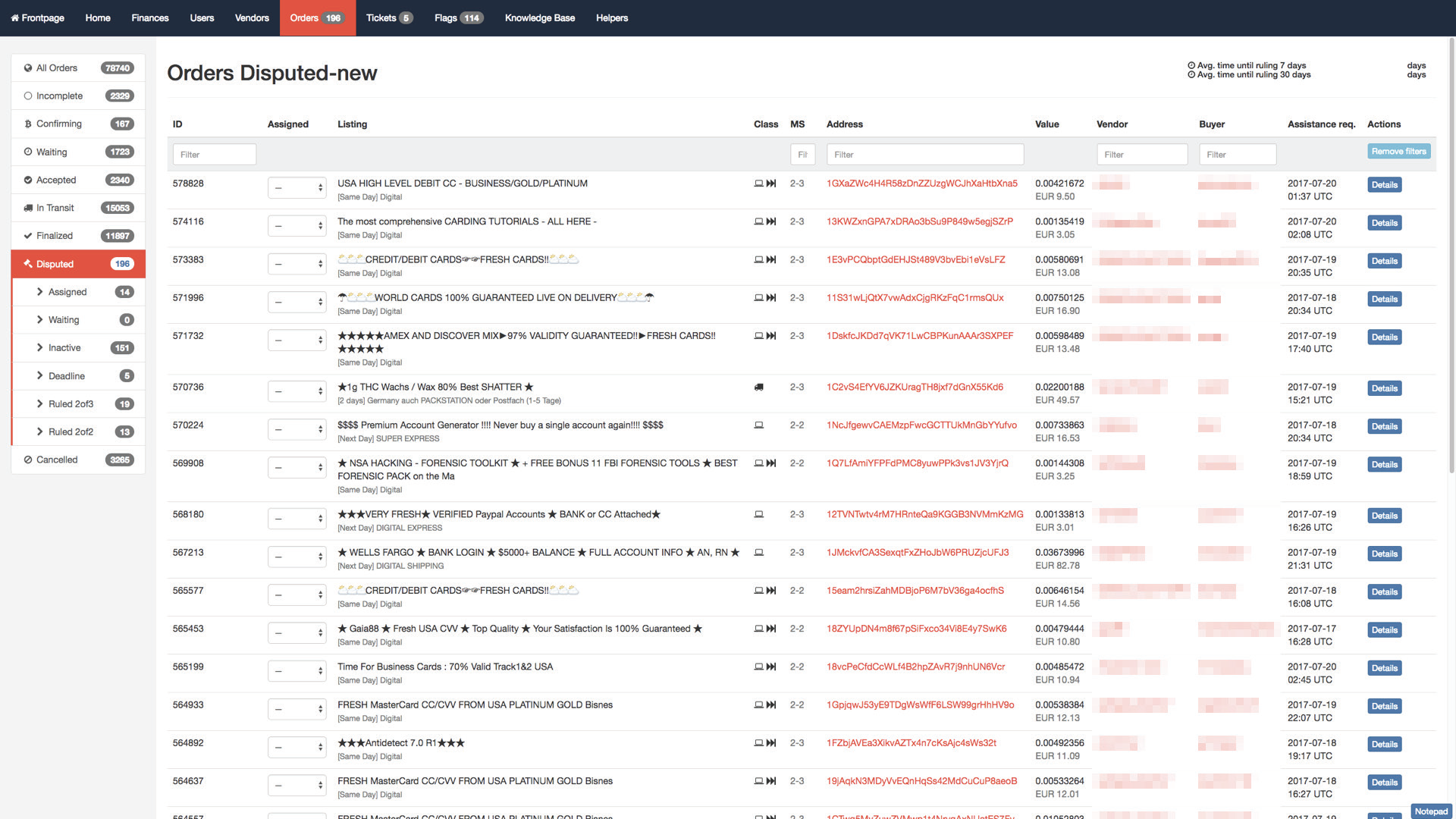

Two Dutch National High Tech Crime Unit (NHTCU) officers described their 10-month investigation into Hansa, once the largest dark-web market in Europe. At its peak, Hansa's 3,600 dealers offered more than 24,000 drug product listings, from cocaine to MDMA to heroin, as well as a smaller trade in fraud tools and counterfeit documents.

During the Operation, Dutch investigators not only identified the two alleged administrators of Hansa's black market operations in Germany but went on to confiscate the two suspects’ accounts and take full control of the site itself.

The NHTCU officers described how they analysed Hansa's buyers and sellers, discreetly altered the site's code to grab more identifying information of those users, and even tricked dozens of anonymous Hansa sellers into opening beacon files on their computers that revealed their locations.

Operation Bayonet is one of the most successful blows to the Dark Web in its short history: millions of dollars’ worth of confiscated bitcoins, over a dozen arrests, a count of the site's top drug dealers, and a vast database of Hansa user information that authorities say should haunt anyone who bought or sold on the site during its last month online.

By secretly seizing control of Hansa rather than merely unplugging it from the Internet, Officer Marinus Boekelo says he and his Dutch police colleagues aimed not only to uncover more about Hansa's unsuspecting users but to also disrupt trust in the system of Dark Web drug and other contraband business.

The operation was assisted by US and German LEA. However, neither the US Department of Justice nor the German Federal Criminal Police Office wanted to share information regarding Operation Bayonet.

The Hansa investigation started with a tip obtained by NHTCU. A security company's researchers believed they had found a Hansa server in the Netherlands data centre of a web-hosting firm.

Boekelo explained that the security firm had somehow found Hansa's development server, a version of the site where new features were tested before live deployment. Although the live Hansa site was protected by Tor, the development server had in some way been exposed online. This is how the security firm discovered it and recorded its IP address.

The Dutch police quickly contacted the web host, demanded access to its data centre and installed network-monitoring equipment that allowed them to record all traffic to and from the machine. They immediately found that the development server was connected to a Tor-protected server at the same location that ran Hansa's live site as well as a pair of servers in another data centre in Germany. Police then made a copy of each server's entire drive, including records of every transaction performed in Hansa's history and every conversation that took place through its anonymized messaging system.

The data interception itself did not expose any of the site's vendors or administrators because all Hansa visitors and admins used pseudonyms. Also, sites protected by Tor can only be accessed by users running Tor, thus anonymizing users’ web connections too.

After investigating all server contents, police found a major clue. One of the German servers contained the two alleged founders' chat logs on the IRC. The conversations stretched back years and amazingly included both admins' full names and one’s home address.

Hansa's two suspected admins, the Dutch cops had discovered, were in Germany—a 30-year-old man in the city of Siegen and a 31-year-old in Cologne. NHTCU contacted German authorities to request the suspects’ arrest and extradition but discovered the pair were already under German police observation and investigation for the creation of Lul.to, a site selling pirated e-books and audiobooks.

NHTCU planned a joint operation with German police. The German police would arrest their suspects for e-book piracy and then secretly take over Hansa without tipping off the market's users. This would ensure they could gather more information regarding the users, especially for determining the identities of the drug sellers.

Interestingly, the Hansa servers the Dutch police were watching suddenly went inactive. NHTCU suspected that their copying of the servers somehow alerted the site's admins. As a result, they might have moved the market to another Tor-protected location and so NHTCU met a stumbling block.

Finally, in April 2017 NHTCU found a lead. The alleged administrators had made a bitcoin payment from an address that had been included in those same IRC chat logs. Using the blockchain analysis software Chainalysis, the police could see that the payment went to a bitcoin payment provider with an office in the Netherlands. NHTCU proceeded to send legal paperwork to that bitcoin payment firm to share the information and identified the recipient of that transaction as another hosting company in Lithuania.

Luckily, the FBI contacted NHTCU informing that they had located one of the servers for AlphaBay, the world's most popular dark-web drug market at the time in the Netherlands. The FBI wanted to close down its operation.

NHTCU expected that after AlphaBay was shut down, its users would go searching for a new marketplace. If the plan worked, AlphaBay's users would migrate to Hansa, which was already under police control.

The Dutch police proceeded by sending a pair of agents to the Lithuanian data centre, taking advantage of the two countries' mutual legal assistance treaty. On June 20, in a carefully timed move designed to catch the two German suspects red handed, the German police raided the two men's homes, arrested them and seized their computers with their hard drives unencrypted. The Germans then informed the Dutch police, who immediately began the migration of all of Hansa's data to a new set of servers under full police control in the Netherlands.

The German police managed to force the two men to hand over their account credentials, including to the Tox peer-to-peer chat system they had used to communicate with the site's four moderators. After three days, Hansa was fully migrated to the Netherlands and under Dutch police control. No users or moderators noticed the change.

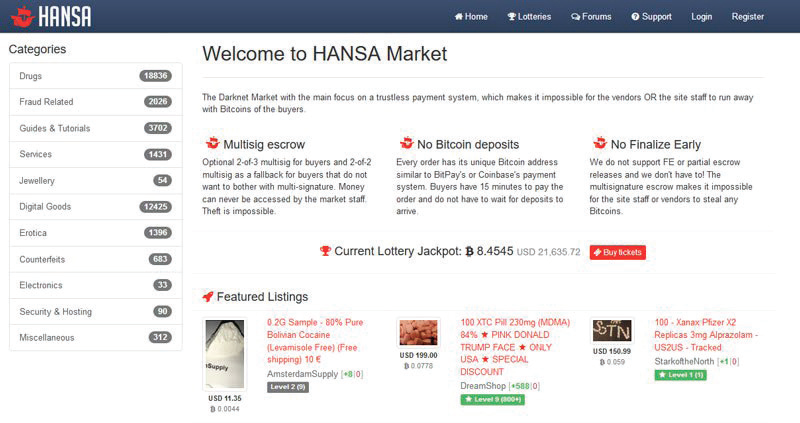

The Dutch police then went on to put Hansa’s users under heavy surveillance. They rewrote the site's code to log every user's password rather than store them as encrypted hashes.

They tweaked a feature designed to automatically encrypt messages with users' PGP keys so it would secretly log each message's full text before encrypting it. In many cases, this allowed police to capture buyers' home addresses as they sent the information to sellers. The site had been set up to automatically remove metadata from photos of products uploaded to the site. Police also altered that function so it would first record a copy of the image with metadata intact. That enabled them to pull geolocation data from many photos that sellers had taken of their illegal ware.

The Dutch police also staged a fake server technical glitch that deleted all photos from the site, forcing sellers to re-upload them, giving Dutch authorities another chance to capture the metadata. With this move it was possible to obtain the geolocation coordinates of more than 50 dealers.

The NHTCU went further by tricking users into downloading and running a homing beacon. Hansa (under NHTCU control) offered sellers a file to serve as a backup key, designed to let them recover bitcoin up to 90 days even if the sites were to go down. The NHTCU replaced that harmless text document with a carefully crafted Excel file. When a seller opened it, their device would connect to a unique URL, revealing the seller's IP address to the police; 64 sellers fell for the trap.

NHTCU analysts studied the logs of real admins' conversations with their moderators and the site's users long enough to convincingly impersonate them. A whole team of officers took turns impersonating the two admins, so when disputes between buyers and sellers escalated beyond the moderators' authority, NHTCU agents were ready to deal with them.

As soon as AlphaBay was taken in early July 2017, drug buyers became impatient and more than 5,000 users flocked to Hansa a day, eight times the normal registration rate, said NHTCU.

After 27 days and about 27,000 transactions, the NHTCU believed they had enough information to arrest and prosecute. NHTCU unplugged Hansa, replacing the site with a seizure notice and a link to NHTCU's own Tor site showing a list of identified and arrested dark-web drug buyers and sellers.

In short, the Dutch police obtained at least some data on 420,000 users, including at least 10,000 home addresses. The data was turned over to Europol to be distributed to other police agencies around Europe and the world. Since the takedown, a dozen of Hansa's top vendors has been arrested.

Dutch police also seized 1,200 bitcoins from Hansa, worth about $12 million. Since Hansa used the bitcoin multi-signature transaction function to protect funds from police seizure, the confiscation was only possible because the NHTCU had taken over the site and sabotaged its code to disable the feature during Hansa's last month online.

The shutting down of Hansa had a stern impact on the remaining users, who did not show up immediately on other drug selling Tor sites like Dream Market. If they did, they recreated their online identities thoroughly enough to escape recognition.